Beyond Redemption – Women of Colour and Abject Art

Our blood, flesh, hair, and tendons compose something so humane that they strike horror in the minds of the purveyors. With abject art, we transgress propriety and cleanliness to appreciate the human body and its functions.

Female bodies – stocked, sold, and merchandized by society, needed to circumvent the burden of purity and innocence. And so, despite concerted efforts from mainstream culture, abject art reestablished itself as a lexicon in feminism. Yet, the overwhelming whiteness of abjection contradicts its purpose. For women of color, abjection simply reaffirms the ideals of white feminism.

Abject art describes artworks that threaten our sense of cleanliness by referencing body parts and bodily functions. The movement began in 1993 at the Whitney Museum, New York. Since then, many theories have developed from the art form. There is an emphasis on blood and other bodily fluids. The movement draws heavy inspiration from Dadaism and Surrealism.

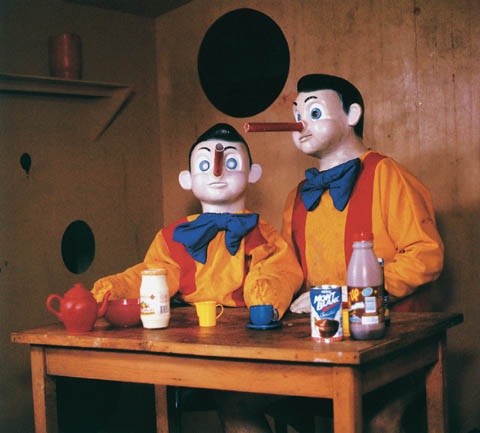

The theory of abjection, proposed by the French-Bulgarian philosopher, Julia Kristeva, argues that the abject body is an antithesis and maybe a solution to objectification. Abjection is a loss of distinction between subject and object, which generates a visceral reaction within the viewers. Kristeva’s theory is best understood through the uncanny-valley phenomenon. The lost comfort and revulsion in the observer are through the breakdown of separation between humans and humanoids.

Abject translates to “state of being cast-off.” Thus, the art movement and the theory have feminist undertones because, from a patriarchal order, the female body exists unnaturally. But, despite the revolutionary assertions of this movement, its canvas is always white. The intact identities of women of color are embedded with a colonial past. Thus, by engaging with abjection, women of color entertain racialized stereotypes already associated with them.

So essentially abject art, an art form designed to challenge the norm has become just another tool to reaffirm the status quo.

For instance, an “unruly woman” onscreen is a diversion from the “ideal woman.” And so, she is re-contextualized as a feminist icon. However, these diversions only work for white women – who represent virtue and chastity. For women of color – hypersexualized and caricatured, this portrayal would lead to further stereotypes.

Jane Alexander’s Butcher Boys captures post-Apartheid Africa. Butcher Boys is a life-size sculpture, currently on display in Johannesburg. Many critics value Alexander’s modernity and abjection as an abnegation of Africa’s consistent struggle with the reconstruction of culture. But, given that her sculptures are understood as embodiments of Apartheid victims, today, it would perpetuate the victimhood asserted on people of color.

Transgressing the taboos of a fragmented, racialized body, is therefore, harder.

So, the comeback of abject art valorizes a cishet, white, and misogynistic society. Occupying abject spaces worries people of color because their Black and Brownness instilled horror and otherness while white supremacy reigned the world.

Minstrelsy perniciously utilized Black people as abjection to whiteness. With its face paint and distortion of Black trauma, American minstrelsy likened Blackness to otherness. And this racial derision can be contextualized as the early beginnings of abject art. As Hannah Black puts it, “American prisons are overwhelmingly Black, American poverty is overwhelmingly Black, American ‘abjection’ is overwhelmingly Black. But contemporary art is overwhelmingly white, seeming to only register Blackness as either an aesthetic modulation or a species of ‘identity politics’, or in other arcane ways that suggest some kind of troubled non- relation.”

In other words, abjection uses characteristics already associated with people of color to celebrate white bodies.

For people of color, our bodies resist the pulpits of white supremacy that built the foundation of our society. So, an art movement that embraces the degradation of the human body also threatens the acceptance of people of color and their humanity. Until racialized stereotypes are reclaimed and devoid of colonial underpinnings, people of color are nothing more than renderings of abjection.